Let us now return to the works of producer Joseph Merhi as we explore his 1988 mind-warping masterpiece Death by Dialogue, a film about a cursed screenplay that alters reality itself.

Some of your universe's critics, unfortunately, do not hail Death by Dialogue as the masterpiece it clearly is. For example, reviewer dead_dudeINthehouse (almost certainly a nom de plume) writes, "I won't even talk about the storyline as it's very BORING -not to say stupid." Reviewer insomniac_rod (possibly a nom de plume?) writes, "Please, stay away from this trash and don't get fooled by the cover art or the premise, which is as dumb as you can get." And reviewer sfhjsth802 (clearly not a nom de plume) writes, "If I were to get technical, this is an awful movie, easily one of the worst ever made."

Read on for the truth about Death by Dialogue...

The film begins as a shadowy, be-Stetsoned figure moves through a cobwebby basement. He opens a trunk, is bathed in an unnatural light, and then literally explodes!

In the next shot, the man is all right, having been knocked off his feet by the explosion. He returns to the chest and opens it to find a journal, which he opens to a random page and starts reading.

He is interrupted by a woman named Mrs. Camden, who is either in her twenties or her fifties. She reminds the man, Mr. Thorn, that he is responsible for taking care of the outside of the house, not the basement. He takes the journal and leaves, walking through a forest at night. “That’s a good one,” he says to himself mysteriously. “Victim 66. What better place to read a script than on a movie set?” (The small, leather bound journal is in fact a movie script.)

Meanwhile, back at the house, Mrs. Camden tells another resident of the house, Mr. Joeveson, that Thorn didn’t find some mysterious thing but they should be taking more precautions.

Outside, Thorn reads more of the script, including a scene in which a character named Mr. Thorn is fired. Curious, he walks through an empty Western movie location at night. The ghost town is filled with fog, and a figure even more mysterious than Thorn appears behind the fog.

“What the hell is the idea behind all of this?” Thorn asks eloquently.

The figure reveals itself to be a woman whom Thorn mistakes for Mrs. Camden. “Oh, I love your get-up,” Thorn quips. “I think you watch too many cartoons. Come on, Camden. Fire me. Fire me!”

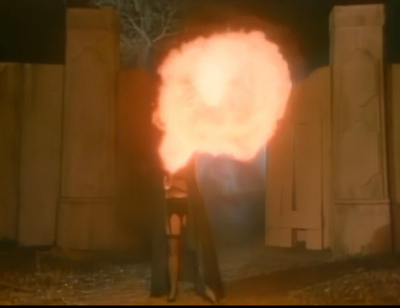

In response, the woman shoots Thorn with a flamethrower.

On fire, Thorn stumbles through the ghost town buildings, finally falling over dead.

The film proper begins with a group of five young people driving along a rural California highway listening to a song with exceptionally fine lyrics.

We’re gonna have a good time

Lookin’ for some fun

I’m riding with my baby

We’re the lucky ones

Rockin’ and a-rollin’ in a club downtown

Cruisin’ a street with the pop-top down

Just got paid, it’s a Friday night

I’ve got a feelin’ the feelin’s gonna turn out right

On the night of our lives

Night of our lives

Night of our lives

Night of our lives

Lose your soul to rock and roll

Party down and lose control

Gettin’ up and getting out

Getting crazy, scream and shout

Rockin’ and a-rollin’, feelin’ the heat

The ground is shakin’ right under your feet

We’re gonna raise hell like never before

We’re gonna party till we just can’t party no more

On the night of our lives

Night of our lives

Night of our lives

Night of our lives

The friends reach the house beside the movie set and are greeted by Mrs. Camden, who runs the house the uncle of one of the friends. The nephew, Cary, goes with Mrs. Camden to see his uncle while the remaining young people separate into two couples. One couple, Lenny (played by Ken Sagoes, who starred as Kincaid in A Nightmare on Elm Street parts 3 and 4) and Shelly, finds a garage with tools to help them fix their car, which appears to have broken down after finding the house. They also find the fateful screenplay in the garage. The other couple, Linda and Gene, walk in the nearby forest, where they discover Thorn’s burnt corpse.

As in all of the best horror films, the story turns to the investigation of the police. A detective and a coroner (who, in time-honored coroner tradition, eats a sandwich while investigating the body, even in the field) determine that Thorn did not die accidentally.

Detective Benjamin interrogates Cary’s uncle, Mr. Joverson, but finds no helpful information. Despite having found a recent horrific murder victim, the young people decide to stay at the property, making their beds in the “Mexican village” section of the movie location. They lounge in a living room and joke about the difference between the “Heimlich maneuver” and a “hymen remover.” Gene says, “I like this place. A regular Motel 6.”

When Cary mentions that the movie sets are full of secret passageways, Gene suggests they play a game of hide and seek. “Better yet, Linda, why don’t you and I go play a game of hide the salami?”

“Why don’t you go hide your salami yourself?” Linda suggests.

Lenny retorts, “Yeah, and as soon as you find it, we’ll find you.” Everyone laughs. (I confess I do not understand this joke, however.)

Meanwhile, Mrs. Camden tells Mr. Joverson that the magic screenplay (titled “Victim 67”) is missing from the trunk in the basement, so he tells her he must find it wherever Thorn may have taken it.

In their room, the friends watch an unidentified horror movie on TV. The movie elicits a philosophical discussion from the group. Gene says seriously, “Imagine getting your head cut off. I mean, does it hurt? Do you feel it? Is it just a sharp pain and then it’s overt, or is it over before you know it, with no pain involved? Come on, think about it, man. You’re sitting there with no head.” He says he really wonders what it would be like.

Lenny says about his own preference for method of death, “I want to go away as a hero. You know, with style. I don’t know how, but I want I want it to be something that people would remember. I’m sorry. Hey, I want the glory?”

“I don’t find any glory in death,” says Shelly.

Later, Shelly reads from the screenplay, which begins evocatively: “She came from nowhere, as if created from the bowels of the universe.” She also reads the part about firing Thorn, which confuses her.

The next day, the friends play volleyball and dance (at the same time). They chase each other through the movie sets, which include the Western town and abandoned mine. They fly a kite and play frisbee as well before they eat lunch with Mr. Joverson. Shelly pays the elderly man a compliment: “Your house is really impressive. I’ve never seen so many animal heads or skins in one person’s home before.”

Cary tells her there are a lot more “heads and skins” on the property, so instead of finishing lunch they immediately take a tour. One room is a veritable museum of taxidermied animals as well as rock samples. Mr. Joverson explains that much of his pre-Colombian artifacts are from the Amazon in South America, where after an emergency plane landing he and his pilot were considered to be “gods sent down from above.” These primitive tribespeople befriended Mr. Joverson and his pilot, and this fact made it possible for him to take many artifacts from the Amazon.

At night, Shelly continues reading the screenplay. We see the scene she is reading, in which a young woman and woman make love in an apparently abandoned barn before they are disturbed by boards on the wall that creak and bleed. (The woman and man onscreen are Gene and Linda, but it is unclear whether Shelly is reading about characters named Gene and Linda.) The couple ignore the loud sounds until Linda is yanked backward by an unseen force and flies through the wall!

Gene dresses and runs out of the barn, searching for his lover. He makes his way through a forest and then stumbles upon a rock band playing a song in the middle of the woods (a not uncommon scene in the late 1980s, I am led to believe).

At the end of the song, the lead guitarist smashes Gene’s head with his guitar.

Shelly puts the script down, finding it amusingly sick.

The next morning, Linda and Gene are nowhere to be found. Shelly speaks with Detective Benjamin, who is visiting to question a resistant Mrs. Camden again. Shelly shows the detective the screenplay. She tells him, “There are scenes appearing where blank pages were before, and I swear that the title keeps changing too.” (Unfortunately, we never learn the new title.) Shelly tells Detective Benjamin the first scene in the screenplay describes Thorn’s death, so they investigate the location where that scene is set.

It is at this point that Shelly realizes the scene she read last night involved Linda and Gene. Reading quickly, she yells to the detective to “Get out of there!” but he suddenly disappears, falling into a hole in the ground while an explosion of dirt appears around him. Shelly runs to him but finds only a grotesquely misshapen face staring at her.

Shelly runs to Cary and Lenny, telling them that the screenplay is both describing and causing the deaths of real people. The three return to the scene of Detective Benjamin’s death but, as is typical both in film and real life, there is no body or evidence of a death. Cary and Lenny are, of course, skeptical. Shelly tries to convince them through emotional histrionics: “I told you it’s in the script. It tells how it killed Mr. Thorn and Gene and Linda, and I just…saw it suck in Detective Benjamin! And it spit him back in my face!”

The film cuts to Lenny reading the screenplay. “How can a script kill someone?” he asks.

Shelly explains that the empty pages fill up with text and the title changes every time someone is killed. (Unfortunately, we have never seen this happen.) They all go into Mr. Joverson’s house and ask what is going on.

Mr. Joverson explains. “You must try to understand what we’re dealing with here. It’s not something that law enforcement officials can help us with.” He tells them about his Amazon visits. On one visit, the local tribe was harassed by an American journalist who wanted to photograph them, so “they became frightened, and then desperate. And they took his life in order to protect their clandestine lifestyle. But shortly after the death of the journalist, terrible things started happening.” (We never learn, perhaps to our benefit, what terrible things ensued.)

The journalist’s remains were sealed in an urn, and Mr. Joverson of course took the urn to return the dead man’s ashes to his native soil. “I agreed to bring it back,” Mr. Joverson says, perhaps insensitively, “thinking it would make a perfect addition to my pre-Colombian art collection.” Eventually, Mrs. Camden cleaned the collection, somehow freeing the evil spirit of the American journalist. Mr. Joverson explains further: “And the life force of that spirit harbored itself in the script of the film that was being done here at the time. That script was entitled ‘Victim.’”

“‘Victim’?” says Shelly. “When I first found the script it was entitled ‘Victim 67.’ And now it’s ‘Victim 70.’ Do you mean to tell me that script has killed seventy people?”

“Over the years, yes,” Mr. Joverson confirms.

Despite Mr. Joverson’s protestations that the script must be contained, Lenny decides to hightail it out of the area, but unfortunately the script has electrified the fence surrounding the property so nobody is able to leave.

Cary and Lenny climb downstairs into the basement and open the trunk that housed the script. Inside is a glowing urn. Cary rolls up the script and attempts to slip it inside the cylindrical urn, but the urn shakes so much he cannot insert it. When he shoves it close to the opening, there is an explosion that throws Cary and Lenny backward.

In the next scene, the young people attempt to burn the screenplay in a campfire. They watch it burn as Shelly says, “I can’t believe all this stuff is happening to us now because of something that happened to someone else almost forty years ago.”

“The whole thing is pretty unbelievable,” Lenny says.

When Lenny puts out the fire, they realize the script is still sitting in the ashes, unharmed.

Apparently to cheer everyone up, Cary sits down and plays the harpsichord, which sends Shelly to sleep. She dreams she is at an idyllic lakeside, where a Formula One race car drives to her (again, I am led to believe this is a not uncommon occurrence in the late 1980s). She runs to the driver and, for unknown reasons, takes off her top.

Then she takes off the driver’s scarf, but this has the evidently unintentional effect of decapitating the driver. Shelly wakes up screaming.

When she wakes, Cary suggests that they write the script to rewrite reality. “I imagine it’s worth a try,” says Mr. Joverson.

They find a typewriter and pitch different ideas about how to solve their problems. Mr. Joverson suggests a power failure at the ranch will eliminate the power source of their problems, so Shelly slowly types a few words and inserts the new page into the screenplay, carefully binding it with little brads. “Say a prayer this one works,” she says as the lights go out.

Everyone gets into Lenny’s car, but they can’t open the gate to the property, which is electrically controlled. They also find a monster in front of the gate, but when Cary tries a to hit it with a branch it vanishes.

Despite their actions, Mr. Joverson has a sudden heart attack and the power comes on at the same time, so they return to the house where Mr. Joverson can rest. Lenny walks to the movie set by himself while the others remain at the house. (Before leaving by himself, he reads the script silently, though we never find out what he is reading.)

Lenny walks through some trees to get to the movie set. He hears a monster growling nearby but continues walking.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Camden investigates a noise in the house, only to find a scimitar-wielding zombie appear in the kitchen. The zombie chases her outside and impales her with the scimitar, lifting her over his head.

At the movie set, Lenny sees the zombie performing a ritual that involves fire and pyrotechnics generated by spinning the scimitar around.

The ritual summons two motorbike riders from hell. Lenny, watching from behind a bush, quips, “Something tells me this isn’t the cavalry.”

Back in the house, Cary finds his uncle on his deathbed. “One must first be content with life before they can rest,” the old man says. “I cannot rest knowing this aberration is wreaking its bestial behavior on us all.”

Cary vows to defeat the evil thing. He and Shelly run through the woods to find Lenny. Before they find him, they hear growling in the forest. Suddenly, something jumps from behind the trees, and Cary shoots it with a rifle. He and Shelly run away, and the monster starts to climb to its feet.

Cary reasons that the evil journalist’s spirit is annoyed because it never received a proper burial. They hatch a plan: stuff the script back into the chest and bury the chest.

After some thrilling action involving wires strung between trees that allow Lenny to destroy one of the biker zombies and a sequence in which Cary shoots the other biker zombie, causing it to explode, everyone returns to the house to bury the screenplay.

After some comedic business about having enough equipment to dig a grave, Lenny returns to the house to find a pick. Unfortunately, Shelly reads the script and realizes the spirit is “now madder than ever.” However, Cary interprets the script as saying that Lenny is mad because he has to find the pick, rather than the spirit being mad. Of course, the spirit quickly appears, thought it is injured by being struck by a random motorbike, for no apparent reason. It moves toward Shelly as she finishes a prayer, and as she says the last word the spirit vanishes.

The film ends abruptly, and the catchy theme song plays over the end credits.

In the late 1980s, one of the most popular horror series was, of course, A Nightmare on Elm Street, which featured a malignant murdered spirit who invaded teenagers' dreams to murder them. Is it too far a stretch to base a horror film around a malignant screenplay with reality-altering powers controlled by the spirit of a journalist murdered by South American tribespeople whose ashes are kept in a sealed urn in a sealed chest in a basement on a movie set? No, of course it is not a far stretch. One might argue that Death by Dialogue is even more grounded than A Nightmare on Elm Street. In any case, both scenarios allow for creative, surrealistic slasher set pieces, and it would be difficult to find set pieces more entertaining than Death by Dialogue's exploding trunks, bodies flying out of barns, and murders by rock band and race car.

Death by Dialogue is one of a string of classics produced by Joseph Merhi, a Syrian-born pizza entrepreneur who pioneered the shot on video format in the late 1980s. Some of his other classic horror films include Epitaph (1987), The Newlydeads (1988), and Hollowgate (1988), all produced before he moved on to produce action films and then to co-produce mainstream films like Rob Reiner's Alex & Emma (2003), David Mamet's Spartan (2004), and Howard Deutch's The Whole Ten Yards (2004). Although Mr. Merhi achieved mainstream success, it is clear his most creative and impassioned films are his early horror videos, films that will be remembered as classics after filmmakers like Mr. Reiner, Mr. Mamet, and Mr. Deutch are long forgotten.